The many applications of 3D scanning

The reasons for 3D scanning are incredibly diverse. Everywhere it’s applied, 3D scanning can measure, document, and record precise data about the physical world. We’ve previously covered ways the entertainment industry is being re-shaped by 3D scanning technology – here are some other cool applications in different realms and disciplines:

Manufacturing

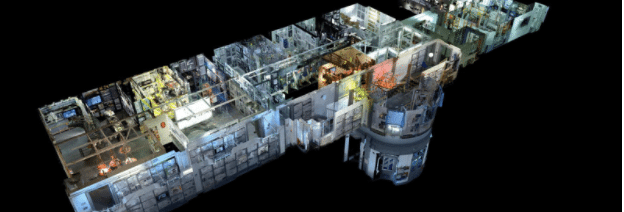

Aerospace was one of the earliest adopters of 3D scanning (and remains a leader) but most earth-bound manufacturing processes now also incorporate 3D laser imaging to inspect equipment or aid in reverse-engineering or prototyping. Fields that involve hazardous environments, like power generation and nuclear, doubly appreciate the hands-off nature and hustle 3D scanning provides.

Medical

In the medical world, one of the greatest benefits of 3D scanning is increasing patient comfort with the customization of wearable devices – braces, implants, prosthetics, etc. It is also non-invasive technology that produces consistent results, requiring little time and no physical contact with patients. The boon of being quick and non-invasive also applies in the field of forensics, where 3D scanning is used to record information about crime and accident scenes.

Perhaps the most cherished application of 3D scanning in medicine is the 3D ultrasound – specifically it’s heart-warming ability to create 3D photos in obstetrics! Although largely considered ‘reassurance’ or ‘entertainment’ scans beneficial for maternal bonding and not much else, the history of 3D ultrasound development is interesting. Pioneered for cardiovascular imaging, 3D ultrasound scanning was first developed in the 1980’s using real-time scanner probes that stacked successive parallel 2D image sections together with their positional info into a computer. Independent of the medical world, computer graphics engineering developed a different approach over the 1990’s that used volume rendering as the basis for a 3D scan, which proved more effective – in fact, much of this body of knowledge originated from computer scientists working for Pixar Animation Studios!

Geographic discovery

In 2015 archaeologists from the University of Illinois undertook the largest archaeological project to ever use LIDAR technology, covering 734 miles over Cambodia’s temple city complex of Angkor Wat in an airborne survey. LIDAR laser technology, when combined with the best 3D scanning software, outstripped previous photogrammetry methods at piercing jungle foliage and capturing the topography beneath, and the archaeologists were able to document huge networks of cities, roads, and water systems buried beneath the jungle vegetation that were previously unknown. Their discovery readjusts historical timelines for the Khmer empire and it’s fall in the 15th century. Further excavations are planned to investigate the full implications of the findings, including the extent of the massive gardens that seem to be indicated by the data.

In 2015 archaeologists from the University of Illinois undertook the largest archaeological project to ever use LIDAR technology, covering 734 miles over Cambodia’s temple city complex of Angkor Wat in an airborne survey. LIDAR laser technology, when combined with the best 3D scanning software, outstripped previous photogrammetry methods at piercing jungle foliage and capturing the topography beneath, and the archaeologists were able to document huge networks of cities, roads, and water systems buried beneath the jungle vegetation that were previously unknown. Their discovery readjusts historical timelines for the Khmer empire and it’s fall in the 15th century. Further excavations are planned to investigate the full implications of the findings, including the extent of the massive gardens that seem to be indicated by the data.

ScanLAB, a design studio in the UK, specializes in artistic projects using a 3D laser scanner or LIDAR. Like the Angkor survey, they’ve scanned cities in Italy and Rome to explore both the underground and topside architectural features. In 2011 they documented ice floes in the Arctic in aid of Greenpeace and in another location captured heavy machinery in the process of deforestation.

Archiving art and artefacts

ScanLAB Projects once scanned an entire exhibition for London’s Science Museum to preserve the gallery once the museum turned the space over for something new.

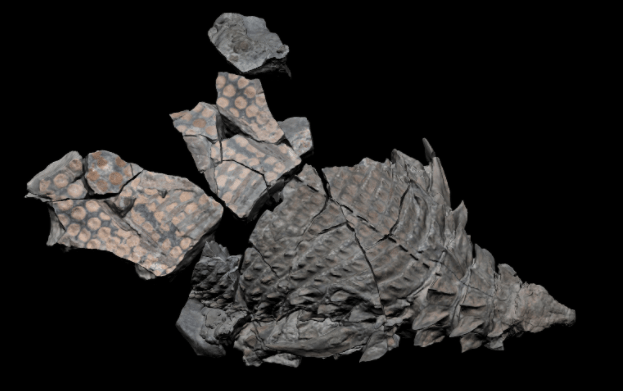

We’ve come a long way since the famous Standford Bunny 3D model scan way back in 1994, and now it’s become commonplace to preserve archeological and historical artifacts digitally through 3D scanning. National Geographic made available this past summer an amazing 3D scan of one of the most impressive fossils ever recovered of a 110 million-year-old nodosaur.

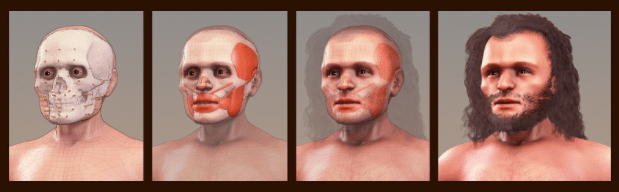

Another classic example of how a 3D scan can aid the scientific community in a creative way is their use in modeling the facial features of our evolutionary ancestors. Today, the modeling takes place in software programs like Blender rather than with clay on a cast form– in 2013 ATOR (Arc-Team Open Research) performed this incredible trick again using the fossil of a cro magnon man. The scanned skull in this case was courtesy of Prof. Dr. Moacir Elias Santos from Brazil, with tissue depth referenced against modern Europeans, taken from De Greef et Al (tip of Heritage Malta).

Another classic example of how a 3D scan can aid the scientific community in a creative way is their use in modeling the facial features of our evolutionary ancestors. Today, the modeling takes place in software programs like Blender rather than with clay on a cast form– in 2013 ATOR (Arc-Team Open Research) performed this incredible trick again using the fossil of a cro magnon man. The scanned skull in this case was courtesy of Prof. Dr. Moacir Elias Santos from Brazil, with tissue depth referenced against modern Europeans, taken from De Greef et Al (tip of Heritage Malta).

Prestigious museums like the Met, the Smithsonian, even Google’s Cultural Institute are embracing 3D scanning as an optimal way to interact, display, and archive art or historical artifacts. Some examples of the practice in rare form include the Smithsonian’s interactive 3D image file of a sculpture depicting the life of the Buddha, highly explorable in the format!

Prestigious museums like the Met, the Smithsonian, even Google’s Cultural Institute are embracing 3D scanning as an optimal way to interact, display, and archive art or historical artifacts. Some examples of the practice in rare form include the Smithsonian’s interactive 3D image file of a sculpture depicting the life of the Buddha, highly explorable in the format!

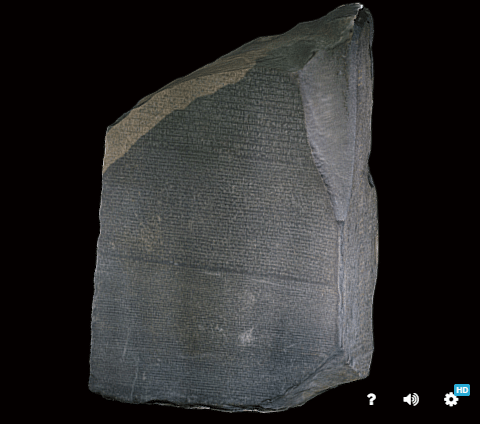

Or this scan of the Rosetta Stone, thanks to Sketchfab and the British Museum:

From the most intimate interfacing of technology with our bodies, to preserving the timelessness of wonders from the past, 3D digitizing spans a use-case range from the most mundane, detail-oriented tasks to those with sweeping emotional impact.

From the most intimate interfacing of technology with our bodies, to preserving the timelessness of wonders from the past, 3D digitizing spans a use-case range from the most mundane, detail-oriented tasks to those with sweeping emotional impact.